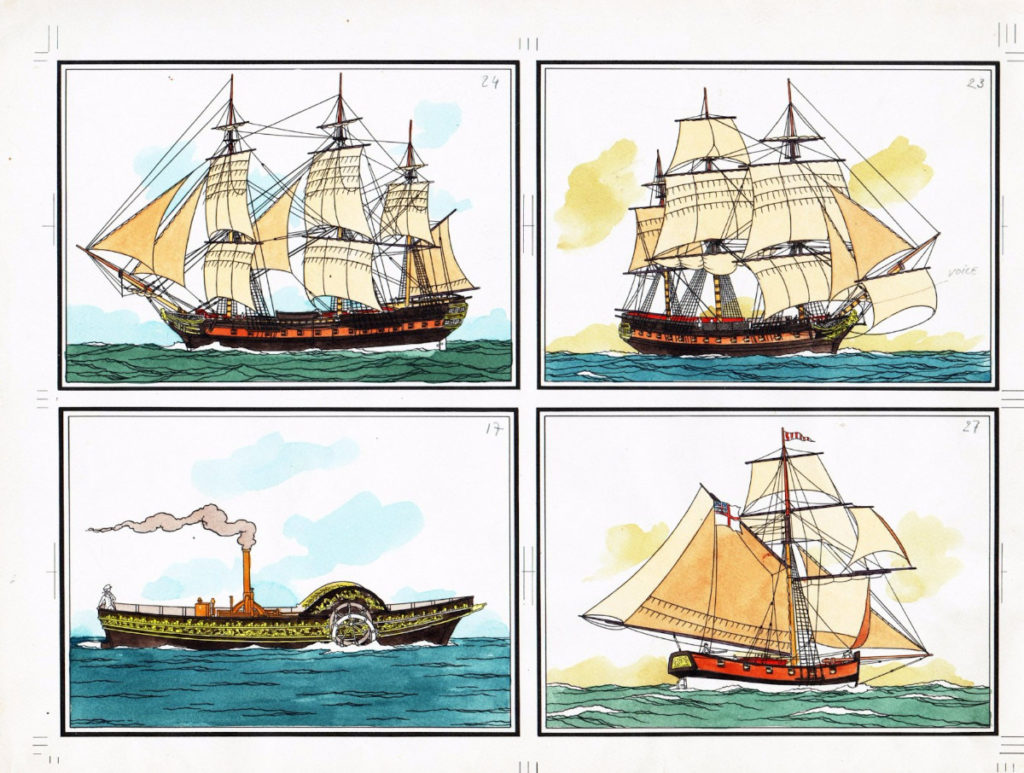

A while ago a drawing of 4 illustrations (completed in watercolor) to be used for the 2nd volume of “L’histoire de la Marine”, namely “L’histoire de la marine de 1700 à 1850165”, got auctioned. Only the coloring was attributed to Bob De Moor, but it’s highly probable that he also made the drawings of the boats unlike what the auction house said.

But something more interesting was revealed on the back of the 31×23.5 cm large drawing: namely some preparatory drawings for Bécassine, which the auction house didn’t seem to be able to pinpoint correctly.

As you might recall from this article, in 1962 (1963?) Bob De Moor had been asked to take over the popular French Bécassine series. Not that surprising, after Pinchon‘s death in 1953, the series continued with other artists, most notably Jean Trubert beginning in 1959. But also De Moor got probed if he was interested.

Bob De Moor himself seemed quite eager to start the project, but although he completed several test drawings, it was Hergé who torpedoed this new adventure. He plainly objected to Bob De Moor’s plan to pursue the Bécassine series. Eventually, Bob De Moor would decline the offer after Hergé told him: “It’s either Tintin or Bécassine”. De Moor continued with Studio Hergé as we all know.

To understand the possible succes of Bécassine, you first need to know what this series was all about

Bécassine, more than just a comic character, it’s an institution

Bécassine is a French comic strip and the name of its heroine, appearing for the first time in the first issue of La Semaine de Suzette on February 2, 1905, initially made as filler for a blank page. Written by Jacqueline Rivière and drawn by Joseph Pinchon, the pages were such a success that new pages regularly appeared, still in the guise of page fillers.

Only in 1913 did Bécassine become the heroine of more structured stories. Still drawn by Pinchon, the stories were then written by Caumery (pseudonym of Maurice Languereau), one of the associates of Gautier-Languereau, the publisher of La Semaine de Suzette. At that time, the character’s real name was revealed to be Annaïck Labornez, her nickname coming from her home village, called Clocher-les-Bécasses.

Between 1913 and 1950, 27 volumes of the adventures of Bécassine appeared. Pinchon drew 25 of them, and Edouard Zier the other two. All 27 were credited as being written by “Caumery”, but after Languereau’s death in 1941, the pseudonym was used by others. After Pinchon’s death in 1953, the series continued with other artists, most notably Jean Trubert beginning in 1959.

Its style of drawing, with lively, modern, rounded lines, would inspire the ligne claire style which Hergé 25 years later would popularise in The Adventures of Tintin.

Bécassine became one of the most enduring French comics of all time, iconic in its home country, and with a long history in syndication and publication. It will make you understand a bit better that this was a huge opportunity for Bob De Moor to put his shoulder, and only his shoulders, under a project.

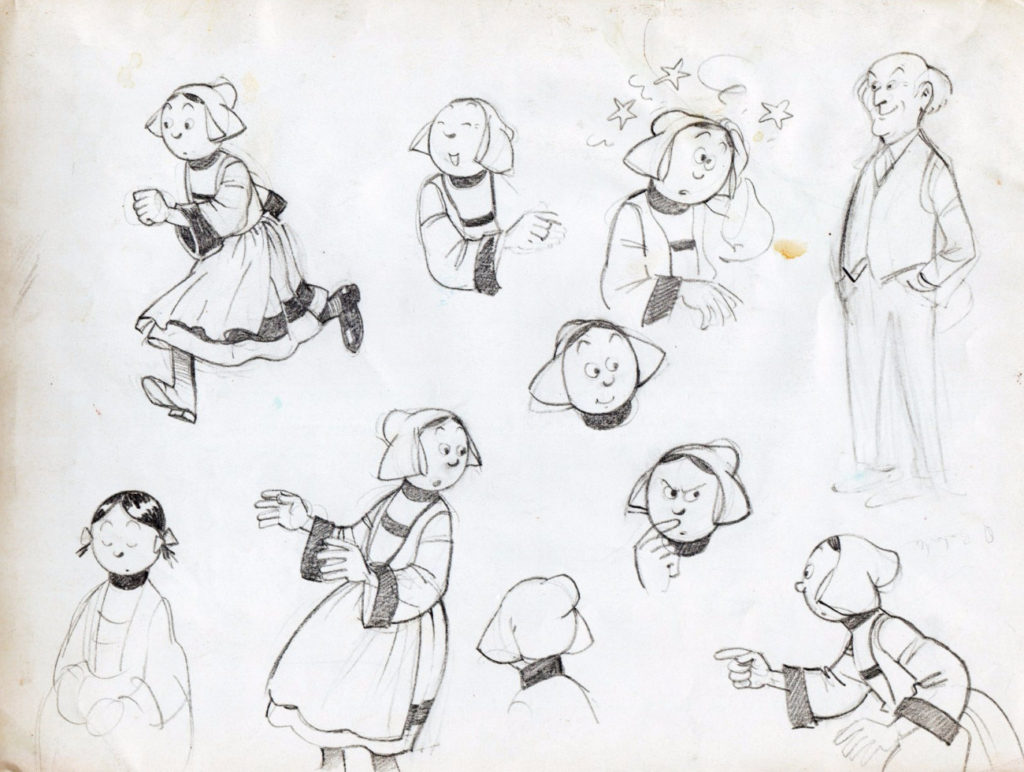

Bob De Moor sketches

The piece of paper itself holds 9 positions of Bécassine plus an extra male figure (unknown to us, if someone has a clue, let us know, it looks like a François Craenhals drawing actually). We see Bécassine running (wearing boots instead of the shoes in this drawing), laughing, recovering (after a blow on the head?), smiling, sleeping (?), looking surprised, the back of her head, being suspicious of something and pointing towards something in surprise.

This seems to be a an already well developed character study, again indicating De Moor really considered having a go at it. Combined with the already known drawings this again shows we would have gotten a Bécassine filled with characters drawn in the Tintin/Barelli style. And looking at it, it could have been a big succes as the drawings are extremely good and Bécassine as a series was well known. As it happens, Annemie De Moor said more or less the same about the drawings she has from this Bécassine experiment when she was interviewed for Ronald Grossey‘s “Bob de Moor: de klare lijn en de golven”.

We can only imagine what would have happened if Bob De Moor would have taken up the task of continuing the Bécassine legacy, but our bet: this would have been a big success (and possibly in Hergé’s mind a clear threat to the continuation of Tintin as De Moor’s input there was tremendously growing as we all know).

A missed opportunity to say the least.