In 1960, the French publisher Editions de l’Ecole published the book “Histoire de mon pays: histoire de Belgique. Degré moyen”. The book, written by E. Billebault and A.-M. de Villers was written for Belgian students of the ‘Degré Moyen’, the intermediate level in the education which would be kids from 6 years and older if we understand correctly. The book counts 64 pages and includes 9 pages featuring all featuring drawings made by Bob De Moor (only 2 were signed as being from Bob De Moor, though but it’s safe to assume that the rest was also by him). The cover was not by Bob De Moor (indeed, although it doesn’t look like a Bob De Moor drawing we did find the original drawing in black and white in the archives of the family De Moor). Remarkably enough Bob De Moor was not credited in the book, except for those 2 signatures.

It was Petja van den Hurk who sent us some pictures you can see here. We’ll show you 9 of these pictures (and expect to see more in the future). In order not to ruin the book, we have not been able taking proper scans, but, as you can see the pictures already give you a very nice idea of the drawings which were included.

The introduction text of the book explains that the drawings in the book are there to provide a better experience for the students. You might as well say it’s the only attractive thing about the book :).

So what do the pictures tell us?

The first drawing on page 4 handles the prehistoric humans. If you look well, you will recognize the typical rock formations in the background which are De Moor‘s trademark.

The text is – as is often the case in these (older) schoolbooks – rather naive telling a quite simplified story of the cavemen and their descendants.

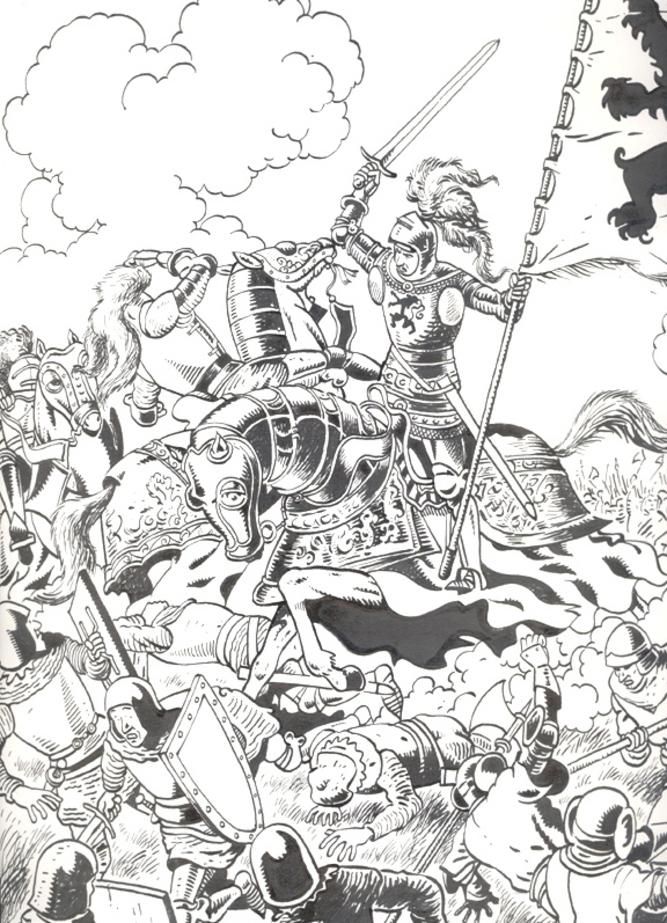

Next is page 28 which offers us a small chef d’oeuvre, as it brings us back to the themes which pleased Bob De Moor the most.

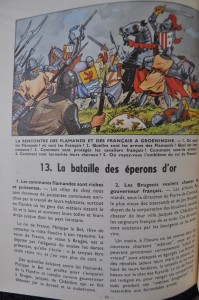

Artistically it clearly refers to the Flemish trilogy Bob De Moor completed. Thematically, the drawing is about the “Battle of the Golden Spurs”, known also as the “Battle of Courtrai”.

The battle was fought on July 11, 1302, near Kortrijk (Courtrai) in Flanders. Since 1973, the date of the battle is also the official holiday of the Flemish community in Belgium.

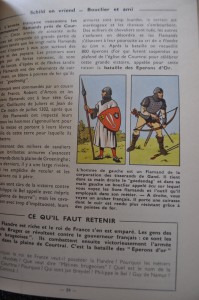

On page 29 De Moor drew a French (right) and a Flemish soldier (left). You’ll see that the Flemish soldier is equipped with a “Goedendag”, a weapon used to crush the skulls of opponents, amongst other things. The French archer has a leather suit which is enforced by metallic points. According to legend, the Flemish identified the French by asking them to pronounce a Flemish phrase, “schilt ende vriend” (English: “shield and friend”) and everyone who had a problem pronouncing this shibboleth was killed (French speaking people would say “skilt end frint” or something similar). Again, this school book says it was a fact whereas it’s common knowledge that this was most probably a legend.

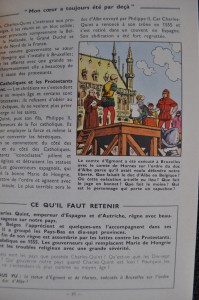

On page 37 Bob De Moor depicts the decapitation of Egmont and Horne, two noblemen. It would be considered the definitive signal to start the the “Dutch Revolution” (1566 or 1568–1648) which was the successful revolution of the Northern, largely Protestant Seven Provinces of the Nether Countries against the rule of the Roman Catholic King Philip II of Spain, who had inherited the region (Seventeen Provinces) from the defunct Duchy of Burgundy. (The southern Catholic provinces, that is Flanders, initially joined in the revolt, but later submitted to Spain.)

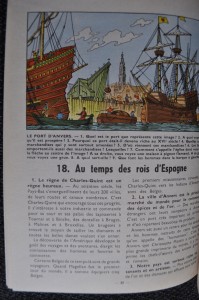

On page 38 Bob De Moor created a drawing of the port of Antwerp, the city where he had lived all of his (childhood) life before moving to Uccle (Brussels) where he would live for the rest of his life.

Considering that the description under the drawing is quite elaborate and also touches on the constructions (including the crane) seen on the drawing, you can be pretty sure that De Moor was told what had to be in the actual drawing. It’s pretty safe to assume that this was the case for all the other drawings as the descriptive texts also show too many details related to the drawing.

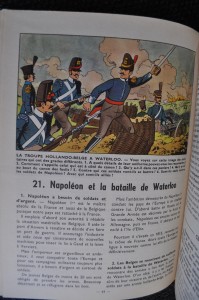

Page 44 mentions Napoleon’s debacle in Waterloo and shows a Belgian-Dutch battalion during the Battle of Waterloo fought on Sunday, 18 June 1815, near Waterloo in present-day Belgium, then part of the United Kingdom of the Netherlands. A French army under the command of Napoleon was defeated by the armies of the Seventh Coalition, comprising an Anglo-allied army under the command of the Duke of Wellington combined with a Prussian army under the command of Gebhard von Blücher.

On page 46 we see a drawing depicting the Belgian revolution against the Dutch occupation, and more exactly the attack on the Park of Brussels. The Belgian Revolution was the conflict which led to the secession of the Southern provinces from the United Kingdom of the Netherlands and established an independent Kingdom of Belgium, in front of where the royal palace is located. Following the installation of Leopold I as “King of the Belgians” in 1831, King William made a belated military attempt to reconquer Belgium and restore his position through a military campaign. This “Ten Days’ Campaign” failed because of the French military intervention.

Page 54 depicts Father Damien taking care of people with leprosy on the island of Molokai. After sixteen years he eventually contracted and died of the disease, resulting in his characterization as a “martyr of charity”.

On October 11, 2009, the Vatican canonized Father Damien. Note that this drawing has a few elements that indicate into the direction of Bob De Moor. You’ll for instance recognize De Moor‘s way of drawing hands (watch closely the women assisting Father Damien) and the plants (the palm tree and the plants behind the assistant). For the rest little makes you think that this is Bob De Moor at work. The fact that he could not use a cartoonesk way of drawing in this history book probably is the reason for this.

The final drawing we present you here is on page 56 and shows the Yser Front, also known as the Flemish Front, which was a section of the Western Front during World War I held by Belgian troops from October 1914 until 1918. The front ran along the Yser river in the far North-West of Belgium and defended a small strip of the country which remained unoccupied.

The front was established following the Battle of the Yser in October 1914, when the Belgian army succeeded in stopping the German advance after months of retreat. The drawing refers to the period when the Belgian army decided to flood a large expanse of territory in front of their lines, stretching as far south as Diksmuide. Note that the Belgian High Command, under King Albert I, vetoed all Belgian involvement in Allied offensives, which he felt to be both costly and ineffective. As a result it were mostly French, Canadian and English soldiers which died on the battlefields.

If you have a copy of this book and were able to scan the pages, don’t hesitate to contact us.